For astronomers, looking at the sky can be like watching an unfamiliar sport on TV. We can’t make sense of what we see but is that because we don’t know the rules or we can’t see all the players? (Or, worst case, we can’t see the players and we don’t know the rules) For us, the players are the stars, and our best guess for the rules is given by the laws of motion and gravity Newton wrote down around 350 years ago.*

Our own Milky Way is a galaxy, a huge collection of stars, and there are billions of galaxies distributed throughout the visible Universe. But if each galaxy is a game, Newton’s rules do not account for the action: stars within galaxies move much too fast for the collective gravitational fields of the stars within each galaxy to be able to hold them together.

Two solutions are possible. If there are large quantities of dark matter in each galaxy the gravitational field of this additional ingredient let us make sense of what we see. Alternatively, if gravity works differently at the huge distances (much larger than on earth or in our solar system) we might be able to manage without dark matter. Dark matter adds extra players in the game; modified gravity changes the rules.

Most (in fact, almost all) astrophysicists prefer dark matter to modified gravity. Neither is perfect: dark matter does a much better job of explaining the properties of the universe on very large scales but there are many open questions about the internal dynamics of galaxies themselves. Physicists have no idea what dark matter would be made of, only that it must be something fundamentally new. Likewise, if gravity works differently on galactic scales we would need a radical rethink of fundamental physics.

The challenge is that we can’t directly measure the gravitational force exerted on a single star by everything else in the galaxy. Newton’s Second Law, “F=ma” tells us that force is proportional to acceleration. Stars move very quickly (the sun travels at 220 km/s relative to the galaxy as a whole; 300 times faster than a speeding bullet) but accelerate – change their motion – very slowly. In roughly 100 millions years time, the sun will be on the other side of the Milky Way with its direction of motion reversed. But the acceleration needed to make this happen changes the sun’s velocity by less than one centimetre per second per year, roughly the speed that an ant walks.

However, Hamish Silverwood (Barcelona) and Richard Easther (Auckland) realised that it may actually be able to detect these tiny changes and thus measure the force exerted on individual stars by all the other mass in the galaxy. This will require measurements of stellar spectra that are accurate to better than one part in a billion or many, averaged measurements. Achieving this will require telescopes and instruments a generation beyond those now in use and to wait for a decade for the changes to accumulate, so this is a project for the 2030s and beyond.

The instruments needed to measure these tiny velocity changes are actually being developed to find planets around distant stars and these planets may also present the biggest challenge to this sort of measurement. As a planet moves in its orbit it induces a small change in the speed of the parent star, like an adult and a child on a see-saw. For an earth-like planet moving round a sun-like star, the change is a few centimetres per second per year and the signal we hope to detect will be roughly this size after a decade of observations. Disentangling the motion induced by planets will be a key challenge. In fact, a group based at Michigan and Harvard were simultaneously and independently working on the same idea and they looked in detail at the challenge of removing the planetary component to reveal the the underlying acceleration.

But once you can directly measure the gravitational forces on stars you can answer a huge range of questions. You can directly test of any imaginable modified gravity theory, which differ in their fine details from a galaxy with dark matter and Newtonian physics. Likewise, if dark matter is holding the galaxy together, the distribution of dark matter may be irregular on small scales, and acceleration measurements would directly map out its distribution in space.

None of this will happen soon – the calculations assumed a ten year baseline and next-generation of high-precision instruments that can be attached to a brace of giant telescopes are now under construction. However, this idea was the subject of a White Paper for the 2020 US Decadal Survey that looked at a wide range of approaches to “direct acceleration” measurements on both cosmological and galactic scales so it is on the radar for planners looking at the cases for building major instruments over the next ten and twenty years. On the other hand, the challenges posed by the motions of stars within the galaxy have been known for over 100 years so even a long wait would be worth it.

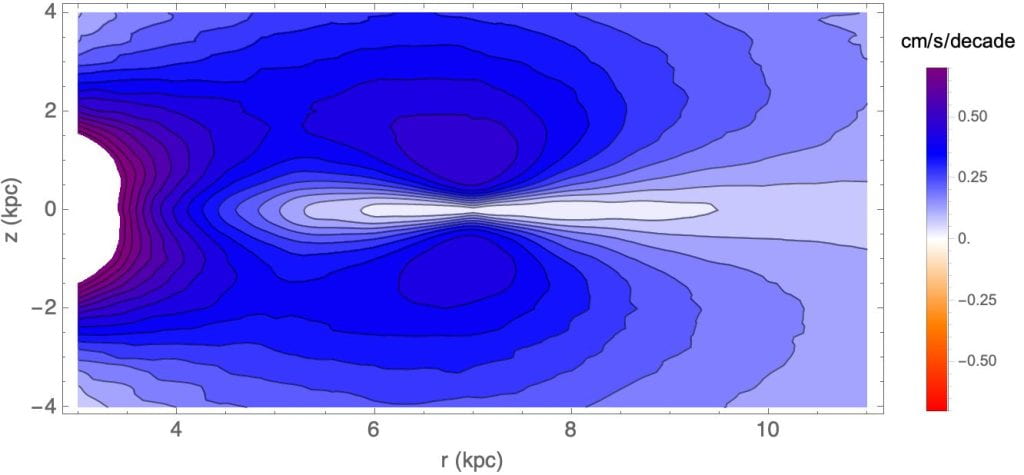

The difference in the expected accelerations from MONDian and Newtonian gravity over the course of a decade seen from a (roughly) sun-like location in a simulated galaxy a little smaller than the Milky Way.

* We know that Einstein’s General Theory of Relativity supersedes Newton’s laws in some circumstances (including descriptions of the global behaviour of the expanding universe) but for the behaviour of stars the two theories make overlapping predictions.

Related Papers

- Inside MOND: Testing Gravity with Stellar Accelerations, Maxwell Finan-Jenkin and Richard Easther • e-Print: 2306.15939 [astro-ph.GA]

- Stellar Accelerations and the Galactic Gravitational Field, Hamish Silverwood and Richard Easther, Publ.Astron.Soc.Austral. 36 (2019) e038 • e-Print: 1812.07581 [astro-ph.GA]